Building a Web App with WebSockets

This post provides detailed, step-by-step instructions on building a realtime web app with WebSockets and Node.js - an interactive cursor position-sharing demo. Building a WebSocket application from scratch provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanics of real-time communication, helping developers understand the challenges and considerations involved in creating responsive, interactive web experiences.

The cursor-sharing demo we’ll build represents a common pattern in modern web applications: real-time collaborative features where multiple users can see each other’s actions simultaneously. This type of functionality forms the foundation for more complex collaborative tools like shared whiteboards, collaborative document editing, multiplayer games, and real-time dashboards. Understanding how to implement basic position tracking and broadcasting provides the groundwork for more sophisticated real-time features.

Running the Demo

Section titled “Running the Demo”> git clone https://github.com/ably-labs/WebSockets-cursor-sharing.git> npm install> npm run startThis demo includes two applications: a web app that we serve through Snowpack, and a Node.js web server. The NPM start task spins up both the API and the web server.

The architecture follows a typical client-server model where the frontend handles user interactions and cursor position tracking, while the backend manages WebSocket connections and message broadcasting. Snowpack serves as our development server, providing fast builds and hot module replacement for a smooth development experience. The separation between the client application and the WebSocket server demonstrates how real-time functionality can be integrated into existing web applications without requiring a complete architectural overhaul.

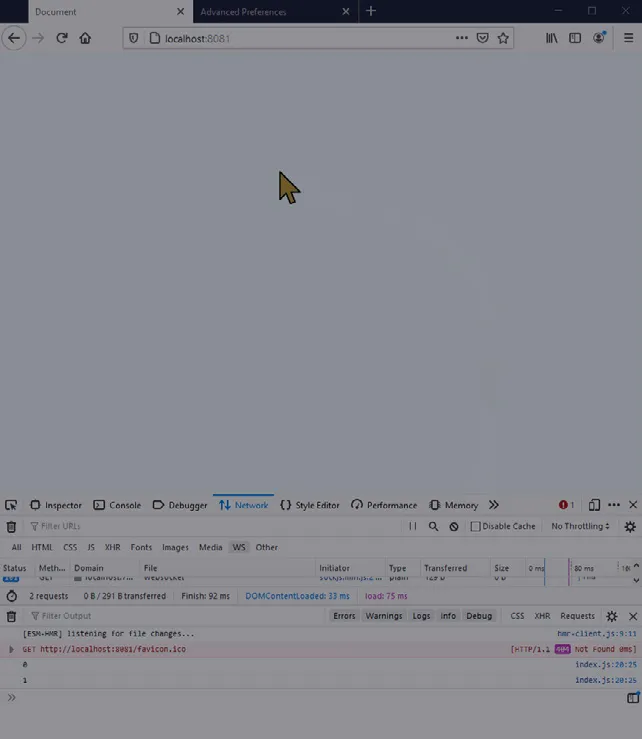

The demo should look as depicted below:

Figure 4.1: Realtime cursor movement powered by the ws WebSockets library

Figure 4.1: Realtime cursor movement powered by the ws WebSockets library

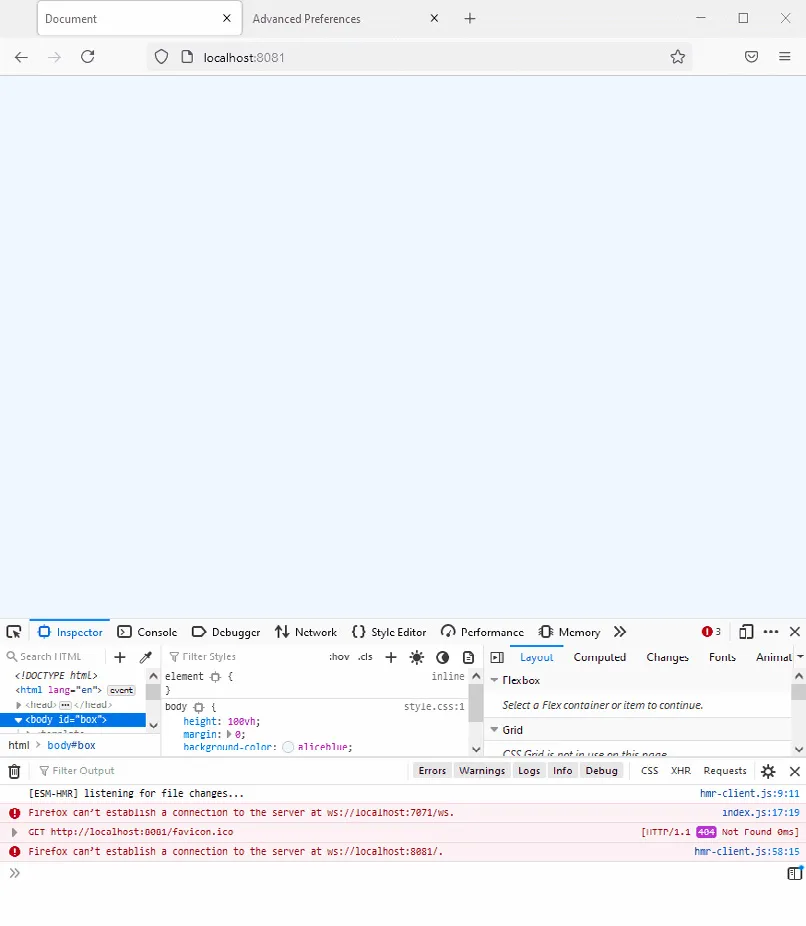

However, if you are running the demo in a browser that does not support WebSockets (e.g., IE9 or below), or if you are restricted by particularly tight corporate proxies, you will get an error saying that the browser can’t establish a connection:

Figure 4.2: Error message returned by the browser when a WebSocket connection

can’t be established

Figure 4.2: Error message returned by the browser when a WebSocket connection

can’t be established

This is because the ws library offers no fallback transfer protocols if WebSockets are unavailable. If this is a requirement for your project, or you want to have a higher level of reliability of delivery for your messages, then you will need a library that offers multiple transfer protocols, such as SockJS.

The limitation of native WebSocket implementations highlights an important consideration in real-world application development: not all environments support WebSockets equally. Corporate firewalls, proxy servers, and legacy network infrastructure can block WebSocket connections, while older browsers may lack WebSocket support entirely. This creates a significant reliability gap that can affect user experience in production environments. For applications that need to reach the widest possible audience or operate in restrictive network environments, implementing fallback mechanisms becomes essential rather than optional. For an analysis of current WebSocket support and whether you still need fallbacks in 2024, see this detailed evaluation.

SockJS — a JavaScript library to provide WebSocket-like communication

Section titled “SockJS — a JavaScript library to provide WebSocket-like communication”SockJS is a library that mimics the native WebSocket API in browsers. Additionally, it will fall back to HTTP whenever a WebSocket fails to connect, or if the browser being used doesn’t support WebSockets. Like ws, SockJS requires a server counterpart; its maintainers provide both a JavaScript client library, and a Node.js server library.

Using SockJS in the client is similar to the native WebSocket API, with a few small differences. We can swap out ws in the demo built previously and use SockJS instead to include fallback support.

Updating the interactive cursor position sharing demo to use SockJS

Section titled “Updating the interactive cursor position sharing demo to use SockJS”To use SockJS in the client, we first need to load the SockJS JavaScript library from their CDN. In the head of the index.html document we built earlier, add the following line above the script include of index.js:

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/sockjs-client@1/dist/sockjs.min.js" defer></script>Note the defer keyword — it ensures that the SockJS library is loaded before

index.js runs.

In the app/script.js file, we then update the JavaScript to use SockJS. Instead of the WebSocket object, we’ll now use a SockJS object. Inside the connectToServer function, we’ll establish the connection with the SockJS server:

const ws = new SockJS('http://localhost:7071/ws');SockJS requires a prefix path on the server URL. The rest of the app/script.js file requires no change.

Next, we have to update the API/script.js file to make our server use SockJS. This means changing the names of a few event hooks, but the API is very similar to ws.

First, we need to install sockjs-node. In your terminal run:

> npm install sockjsThen we need to require the sockjs module and the built-in HTTP module from Node. Delete the line that requires ws and replace it with the following:

const http = require('http');const sockjs = require('sockjs');We then change the declaration of wss to become:

const wss = sockjs.createServer();At the very bottom of the API/index.js file we’ll create the HTTPS server and add the SockJS HTTP handlers:

const server = http.createServer();wss.installHandlers(server, { prefix: '/ws' });server.listen(7071, '0.0.0.0');We map the handlers to a prefix supplied in a configuration object (‘/ws’). We tell the HTTP server to listen on port 7071 (arbitrarily chosen) on all the network interfaces on the machine.

The final job is to update the event names to work with SockJS:

// ws.on('message', /* ... */) will become ws.on('data', /* ... */)// client.send(outbound); will become client.write(outbound);And that’s it, the demo will now run with WebSockets where they are supported; and where they aren’t, it will use Comet long polling. This latter fallback option will show a slightly less smooth cursor movement, but it is more functional than no connection at all!

Running the demo with SockJS

Section titled “Running the demo with SockJS”If you’ve been following along with the tutorial, then you can run:

> npm install> npm run startIf not, you can clone a working version of the demo from: https://github.com/ably-labs/websockets-cursor-sharing/tree/sockjs.

> git clone -b sockjs https://github.com/ably-labs/WebSockets-cursor-sharing.git> npm install> npm run startThis demo includes two applications: a web app that we serve through Snowpack, and a Node.js web server. The NPM start task spins up both the API and the web server.

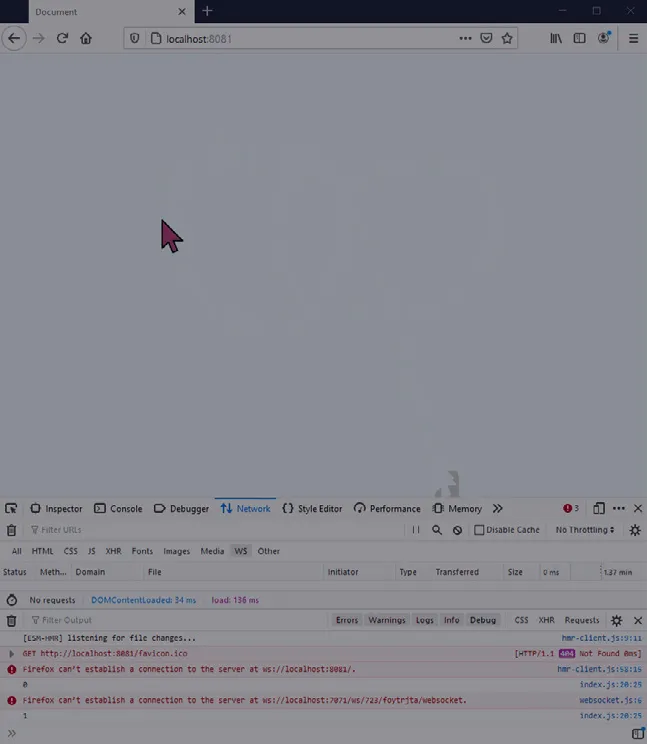

The demo should look as depicted below:

Figure 4.3: Realtime cursor movement powered by the SockJS WebSockets library

Figure 4.3: Realtime cursor movement powered by the SockJS WebSockets library

Scaling the web app

Section titled “Scaling the web app”You might notice that in both examples we’re storing the state in the Node.js WebSocket server — there is a Map that keeps track of connected WebSockets and their associated metadata. This means that for the solution to work, and for every user to see one another, they have to be connected to the same WebSocket server.

The number of active users you can support is thus directly related to how much hardware your server has. Node.js is pretty good at managing concurrency, but once you reach a few hundred to a few thousand users, you’re going to need to scale your hardware to keep all the users in sync.

Scaling vertically is often an expensive proposition, and you’ll always be faced with a performance ceiling of the most powerful piece of hardware you can procure. Additionally, vertical scaling is not elastic, so you have to do it ahead of time. You should consider horizontal scaling, which is better in the long run — but also significantly more difficult. Ably has a good architectural document explaining how they have approached vertical vs horizontal scalability for WebSockets.‘

What makes WebSockets hard to scale?

Section titled “What makes WebSockets hard to scale?”WebSockets are fundamentally hard to scale because connections to your WebSocket server need to be persistent. And even once you’ve scaled your server layer, you also need to provide a solution for sharing data between the nodes. Connection state needs to be stored out-of-process — this usually involves using something like Redis, or a traditional database, to ensure that all the nodes have the same view of state.

The persistent nature of WebSocket connections creates unique challenges that don’t exist with traditional HTTP request-response patterns. Each WebSocket connection maintains state on the server, consuming memory and processing resources even when idle. This stateful nature means that load balancing becomes more complex - you can’t simply round-robin requests across servers as you would with stateless HTTP traffic. Instead, you need sticky sessions or more sophisticated routing mechanisms to ensure that clients can maintain their connections and receive all relevant messages.

Moreover, when scaling horizontally, the challenge of message broadcasting becomes exponentially more complex. In our simple cursor-sharing demo, broadcasting a cursor position to all connected clients is straightforward when they’re all connected to the same server. However, when clients are distributed across multiple servers, you need a message bus or pub/sub system to ensure that messages from one server reach clients connected to other servers. This inter-server communication adds latency and complexity to your architecture, requiring careful design to maintain the real-time performance that WebSockets are meant to provide.

In addition to having to share state using additional technology, broadcasting to all subscribed clients becomes difficult, because any given WebSocketServer node knows only about the clients connected to itself.

There are multiple ways to solve this: either by using some form of direct connection between the cluster nodes that are handling the traffic, or by using an external pub/sub mechanism. This is sometimes called “adding a backplane” to your infrastructure, and is yet another moving part that makes scaling WebSockets difficult.

See WebSockets at Scale for a more in-depth read about the engineering challenges involved in scaling WebSockets. For production applications, you might want to consider using a realtime platform like Ably that is architected for scaling WebSockets.